The Murrays of Elibank - Blackbarony

A history of Peeblesshire by William Chambers (1800-1883)

THE MOST NOTED ESTATE in Eddlestone parish, Peeblesshire, is that of Darn Hall, the property of the Murrays, Lords Elibank. The name Darn Hall is modern ; or at least is employed for the first time in 1536. It has superseded the more historical designation, Blackbarony, which, however, was not the earliest by which the property is styled in the family writs. The oldest recorded name is Haltoun or Haldoun, now entirely unknown, or only distinguishable in the corrupted form of Hatton-knowe, which is applied to one of the farms. Occasionally, the property was called Halton-Murray, to distinguish it probably from another Halton in possession of the Lauders, whose property, as far as we can judge, lay further down the valley. The Murrays, descended from the Moreffs or Moravias, who figure in the Ragman Roll, come into notice as proprietors in this quarter in the fourteenth century. At the beginning of the fifteenth, that is in 1412, a writ refers to ' George de Moravia Dominus de Halton;' and another writ, under date 1518, mentions 'the barony of Haltoun, alias the Blackbarony,' by which the two designations are identified as applying to the same property.

This ancient domain of Haltoun or Blackbarony was very extensive ; for it appears to have, at one time, embraced nearly the whole of the lands, north and south, in the upper section of the strath of Eddleston Water. For the sake of distinction, the estate was ordinarily divided into two parts. Blackbarony was that portion lying on the north or right bank of the Eddleston, while Whitebarony was that on the left ; but these were only terms of convenience ; the whole was but one property, possessed by the Murrays, whose residence was at Darn Hall, on the Blackbarony side of the valley.

John Murray of Blackbarony, the eighth laird in the family roll, is reputed to have been a man of great bravery and fortitude, qualities which he evinced by following James IV. to the fatal field of Flodden, and there perishing with him. He was succeeded by his only son, Andrew, who added to the family possessions by acquiring part of Ballencrief, in Haddingtonshire, a portion of which lands had been previously acquired by his father. From Andrew several lines of Murrays are descended. He had four sons and four daughters, but not to confuse our narrative, we shall specify only the first and third son, John his heir, and Gideon, the progenitor of the Murrays of Elibank. John, who succeeded on the death of his father, received the honour of knighthood from James VI in 1592. Sir John Murray acquired some local celebrity for enclosing the hitherto open lands on his estate with stone walls, the first of the kind in Peeblesshire, and from which operations he became popularly known as the Dyker. We have no doubt that the Dyker was a man in advance of his time, who saw the importance of fencing, planting, and otherwise improving his extensive property. Archibald, his son, who succeeded as heir, was created a baronet of Nova Scotia, with continuation to his heirs-male, by Charles I, May 15, 1628. Sir Archibald, the first baronet, was succeeded by his eldest son, Sir Alexander Murray, who was appointed high-sheriff of Peeblesshire by Oliver Cromwell.

From about this period, a living interest is attached to the Murrays of Blackbarony. They are frequently mixed up with public events, take a lead in the county, and keep house with considerable degree of state at Darn Hall. This edifice, originally a border tower, situated in a dcrn or concealed place, and hence its name, had already been amplified by additions adapted to the growing distinction of the family. One of the lairds, possibly the Dyker, had planted a double row of limes, extending down the slope to the outer access to the grounds, forming a straight and broad avenue to the mansion.

Except Traquair, there was nothing grander in its way in Peeblesshire than Darn Hall, and it seems to have quite fitted the taste for magnificence of Sir Alexander Murray, the second baronet. It is related of this stately personage that, on the occasion of giving entertainments at Darn Hall, he equipped his servants and tenants in liveries, which he kept for the purpose, and placed them on each side of the grand avenue, all the way to the door of his residence ; and that when they had so done their duty, they, by a back-way, reached the house, and performed over again in the vestibule and staircase. It is further alleged, that having seen the king of Portugal walk with a shuffling gait in consequence of weakness in his ankles, Sir Alexander always afterwards, as a mark of courtly manners, affected the same awkward species of locomotion. But the thing on which he chiefly prided himself was something superior to either his suite of attendants or his mode of walking. One day, a gentleman speaking to him of old families, he replied : ' Sir, there are plenty of old families in this country, in France, Germany, and, indeed, all over the world ; but there are only three Houses — the Bourbons of France, the Hapsburgs of Austria, and the Murrays of Blackbarony !'

With all this love of show and fancied greatness, Sir Alexander had the address so to economise expenditure as to rear a large family of children, and settle them all respectably. He was twice married. By his first wife, he had two sons and two daughters. Archibald, the eldest son, was his heir, and Richard, the second son, acquired Spitalhaugh. Of his second marriage, there was one son, John (to whom he assigned the lands afterwards known as Cringletie), and five daughters. Two of these young ladies were married to gentlemen in the county. Janet became the wife of John Hay of Haystoun, of whose son, Dr James Hay, and other members of his numerous family, something has already been said. The other was married to Murray of Murray's Hall, now Halmyre. The story of the courtship of Janet — or Jean, as she is styled in the legend — may not perhaps be entirely vouched for ; but is too illustrative of old manners, and of the finesse which was sometimes employed by mothers of young ladies of quality in securing an eligible suitor, to be omitted.

One day — so goes this popular tradition — as Sir Alexander Murray was strolling down the avenue, he saw the Laird of Haystoun, mounted on his white pony, approaching, as if with the intention of visiting Darn Hall. After the usual greetings, Murray asked Haystoun if that was his intention. ' Deed, it 's just that,' quoth Haystoun, * and I '11 tell you my errand. I am gaun to court your daughter Jean.' The Laird of Blackbarony (who, for a reason that will afterwards appear, was not willing that his neighbour should pay his visit at that particular time) gave the thing the go-by, by saying that his daughter was ower young for the laird. ' E'en 's you like,' quoth Haystoun, who was somewhat dorty, and who thereupon took an unceremonious leave of Blackbarony, hinting that his visit would perhaps be more acceptable somewhere else. Blackbarony went home, and immediately told his- wife what had passed. Her ladyship, on a moment's reflection, seeing the advantage that was likely to be lost in the establishment of her daughter, and to whom the disparity of years was no objection, immediately exclaimed : ' Are you daft, laird? Gang awa' immediately, and call Haystoun back again.' On this, the laird observed— (and this turned out the cogent reason for his having declined Haystoun's visit) — ' Ye ken, my dear, Jean's shoon 's at the mending.' (For the misses of those days had but one pair, and these good substantial ones, which would make a strange figure in a drawing-room of the present day.) ' Ye ken Jean's shoon 's at the mending.' ' Hoot awa, sic nonsense,' says her ladyship ; ' I '11 gie her mine.' ' And what will ye do yoursel 1 ' ' Do 1 ' says the lady : ' I '11 put on your boots ; I Ve lang petticoats, and they will never be noticed. Rin and cry back the laird.' Blackbarony was at once convinced by the reasoning and ingenuity of his wife ; and as Haystoun's pony was none of the fleetest, Blackbarony had little difficulty in overtaking him, and persuading him to return again. The laird having really conceived an affection for his neighbour's daughter, the visit was paid. Jean was introduced in her mother's shoes ; the boots were never noticed ; and the wedding took place in due time, and was celebrated with all the mirth and jollity usually displayed on such occasions. The union turned out happily, and from it, as has been said, sprung the present family of Haystoun.

Sir Alexander was succeeded by his son, Sir Archibald, the third baronet, who comes frequently into notice in the reign of Charles II., as lieutenant-colonel of the militia regiment of Linlithgow and Peeblesshire, employed during that period of civil commotion. Surviving the Revolution, he left a son, Alexander, his heir, and four other sons, likewise two daughters. There now ensues a revolution in the family. Three of the younger sons died unmarried ; their next elder brother, Captain Archibald Murray, was married, and had a daughter, Margaret. Sir Alexander, the laird, was married, but had no children, and resigned Blackbarony to Margaret his niece, who married John

Stewart of Ascog. The baronetcy devolved on the heirs of Richard Murray of Spitalhaugh, a property long since out of the family (see NEWLANDS). With the descendants of Richard, the baronetcy still remains, though those who enjoy it have no territorial connection with the county.

Leaving Blackbarony in possession of the Stewarts, we revert to Gideon Murray, whose ennobled descendants were destined to recover the old family seat of Darn Hall. Gideon, the third son of Sir John Murray, the Dyker, was reared for the church, and was appointed to the office of ' chanter of Aberdeen.' Happening to kill a man — not an unusual occurrence in the early part of the reign of James VI. — he was imprisoned in Edinburgh Castle, but was afterwards pardoned, and for some recommendable qualities received a charter of the lands of Elibank, county of Selkirk, March 15, 1594-95. Subsequently, he. had grants of other lands, and in him centred the lands of Ballencrief. In 1605, he received the honour of knighthood ; was constituted treasurer-depute in 1611 ; and in 1613, was appointed one of the Lords of the Court of Session.

From these and other circumstances, Sir Gideon, or, as he was familiarly called by the country-people, Sir Judane, Murray, was evidently a man of high trust in the reign of James VI., and was able to keep house, first at the Provostry of Creighton, and afterwards at Elibank, in a manner outshining his relatives at Darn Hall. As he was noted for his reparations on the royal palaces and castles, there can be little doubt that he either wholly built the castle of Elibank, or extended it from the condition of an old border tower. Now a shattered ruin, occupying a commanding situation on the south bank of the Tweed, Elibank still shews signs of having been a residence of a very imposing character, defensible according to the usages of the period at which it was inhabited. Here, then, when not engaged in state affairs, Sir Gideon lived with his family. He had married Margaret Pentland, and had three sons, Patrick, William, and Walter, and one daughter, Agnes. How the circumstance of having only one daughter is to be reconciled with the story related by Sir Walter Scott, in his Border Antiquities, afterwards versified by James Hogg, and now universally credited, we are at a loss to say. We may at least repeat this amusing legend in Scott's own words :

' The Scotts and Murrays were ancient enemies ; and as the possessions of the former adjoined to those of the latter, or lay contiguous to them on many points, they were at no loss for opportunities of exercising their enmity "according to the custom of the Marches." In the seventeenth century, the greater part of the property lying upon the river Ettrick belonged to Scott of Harden, who made his principal residence at Oakwood Tower, a border-house of strength still remaining upon that river. William Scott (afterwards Sir William), son of the head of this family, undertook an expedition against the Murrays of Elibank, whose property lay at a few miles distant. He found his enemy upon their guard, was defeated, and made prisoner in the act of driving off the cattle, which he had collected for that purpose. Our hero, Sir Gideon Murray, conducted his prisoner to the castle, where his lady received him with congratulations upon his victory, and inquiries concerning the fate to which he destined his prisoner. " The gallows," answered Sir Gideon — for he is said already to have acquired the honour of knighthood— " to the gallows with the marauder." " Hout na, Sir Gideon," answered the considerate matron in her vernacular idiom ; " would you hang the winsome young Laird of Harden, when ye have three ill-favoured daughters to marry?" "Right," answered the baron, who catched at the idea ; " he shall either marry our daughter, mickle-mouthed Meg, or strap for it." Upon this alternative being proposed to the prisoner, he, upon the first view of the case, stoutly preferred the gibbet to " micklemouthed Meg," for such was the nickname of the young lady, whose real name was Agnes. But at length, when he was literally led forth to execution, and saw no other chance of escape, he retracted his ungallant resolution, and preferred the typical noose of matrimony to the literal cord of hemp. Such is the tradition established in both families, and often jocularly referred to upon the borders. It may be necessary to add, that mickle-mouthed Meg and her husband were a happy and loving pair, and had a very large family.'

Sir Gideon's only daughter was certainly married to young Scott of Harden, but it is as true that the marriage did not take place hurriedly, but was the subject of a deliberate contract, to which there were four assenting parties — Sir Gideon Murray and Walter Scott of Harden, as the two fathers, and William Scott, younger of Harden, and Agnes Murray, the two to be united. This contract, existing among the Elibank Papers, is a very curious document. It consists of a series of sheets of paper pasted together, forming a strip about ten inches broad and eight feet long, well covered on one side with writing, and defines, among other matters, the tocher to be given with Agnes, which was seven thousand merks Scots (£388, \js. o//. sterling). The deed purports to be executed at the ' Provost's place of Crighton,' July 14, 1611. The young lady subscribes with a bold hand, ' Agnes Morray.' Walter Scott of Harden, the fatherin-law, was so illiterate as to be unable to sign his name, and adhibits his consent as follows : ' Walter Scott of Harden, with my hand at the pen, led be the notaries underwritten, because I can nocht write.' William Scott, his son, subscribes without assistance. From another old writ, it is seen that ' Dame Margaret Pentland,' wife of Sir Gideon, and mother of Agnes and of the first Lord Elibank, had no more knowledge of letters than Walter Scott of Harden, for she subscribes by a notary because she ' can nocht write.'

Placed in the position of treasurer-depute, Sir Gideon Murray is said to have acquitted himself as an able financier, on the occasion of the visit of James VI. to Scotland in 1617, for which and other services he secured the confidence of the king, who, as a mark of favour, bestowed on him the gilt cups and other ' propynes ' which had been gifted to his majesty by the cities of Edinburgh, Glasgow, and Carlisle.

So highly did the king esteem Sir Gideon, that when on one occasion he happened to let his glove fall, his majesty stooped and gave it to him again, saying : ' My predecessor, Queen Elizabeth, thought she did a favour to any man who was speaking to her when she let her glove fall, that he might take it up, and give to her again ; but, sir, you may say a king lifted up your glove.' If there be any truth in this story, Sir Gideon had reason to feel that the friendship of James was far from secure. Capricious, and influenced by parasites, the king believed a malicious accusation against Sir Gideon, and had him seized and sent a prisoner to Scotland to be tried — an indignity which so preyed upon him that he abstained from food for several days, and sinking into a state of stupor, died on the 28th of June 1621. Sir Gideon was succeeded by his eldest son, Sir Patrick Murray, who was created a baronet in 1628, and advanced to the peerage as Lord Elibank, 1643. He was succeeded by Patrick the second, and Patrick the third Lord Elibank. The son and successor of the last mentioned was Alexander, the fourth baron, who left five sons — Patrick, who succeeded as fifth Lord Elibank, George, Gideon, Alexander, and James. We pause a moment to refer to the youngest, the Hon. James Murray, a general in the army, who was governor of Canada in 1763, and in 1781 stood a siege in Fort St Philip, Minorca, when that island was invaded by the French under the Due de Crillon. An incident occurred on this occasion, worthy of being noticed in the family history. Failing to secure the fort by force of arms, the Due de Crillon sent a secret message to General Murray, offering to pay him ;£ 100,000 sterling for the surrender of the place.1 Indignant at this attempt to corrupt his integrity, he sent the following spirited reply, dated October 16, 1781 :

' When your brave ancestor was desired by his sovereign to assassinate the Due de Guise, he returned the answer which you should have done, when you were charged to assassinate the character of a man whose birth is as illustrious as your own or that of the Due de Guise. I can have no further communication with you but in arms. If you have any humanity, pray send clothing for your unfortunate prisoners in my possession ; leave it at a distance, to be taken up by them, because I will admit of no contact for the future, but such as is hostile to the most inveterate degree.' To this the duke replied : ' Your letter restores each of us to our places ; it confirms me in the high opinion I have always had of you. I accept your last proposal with pleasure.' — The general, as is well known, bravely held out until famine and disease obliged him to capitulate, Feb. 5, 1782. 'I yield to God and not to man,' was the memorable saying of General Murray, on rendering up the emaciated defenders of the garrison, whose appearance drew tears from the French officers and soldiers.

Patrick, fifth Lord Elibank, was an accomplished man of letters, and commemorated as the friend of Dr Samuel Johnson, whom he entertained at Ballencrief, on his visiting Edinburgh. He died in 1778, and was succeeded by George, his brother, an eminent naval officer, who, at his decease in 1785, was succeeded by his nephew, Alexander, son of Gideon Murray, D.D., prebendary of Durham. Alexander, the seventh Lord Elibank, bred an officer in the army, will be remembered as commander of the local militia of Peeblesshire. There having been no issue

of the marriage of Stewart of Ascog and Margaret Murray, the Blackbarony estate, so far as not disposed of, went in virtue of a deed of entail to Alexander, seventh Lord Elibank, in whom the several properties belonging to the family in Selkirkshire, Haddingtonshire, and Peeblesshire, were united ; whereupon the Elibank branch of the Murrays was reinstated in Darn Hall. This peer died in 1820, and was succeeded by his eldest son, Alexander, as eighth baron. On the decease of that nobleman in 1830, the title and property devolved on his eldest son, Alexander-Oliphant, the present peer.

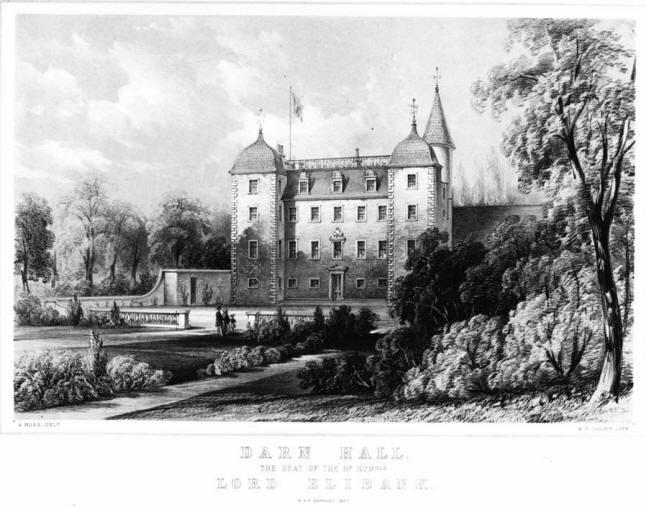

The Murrays of Elibank, whose history we have very faintly sketched, long since vacated the old castle of their ancestor, Sir Gideon, and leaving it to sink to decay, have returned permanently to the original residence of Darn Hall. By the tastefulness of its present proprietor, the house has been greatly extended and improved. As shewn in the preceding cut, fig. 48, it is a massive square mansion, ornamented by corner turrets in the old French-chateau style. It contains some good family pictures, including one of Patrick, fifth Lord Elibank. Around the house, the grounds are very beautiful ; while that old spacious avenue of limes, though now disused as an approach, remains a striking object in the scene, reminding us of John the Dyker, and his grandson, Sir Alexander the Magnificent.

Since possessed by these worthies, the estate of Blackbarony has undergone various mutations, and is now considerably less than it was. Milkiston, which had been disposed of, has been re-attached by the present Lord Elibank at a cost of about ;£ 1 2,000. Latterly, increased by this means, and much improved in various ways, the entire property within the parish, in 1863, had a valued rental of £1783, 2s.

Halton-Murray, or Blackbarony, might almost be called the parent estate in the parish, for from it most other properties have been excavated. It began to be disposed of in the early part of the eighteenth century. To judge from the valuation rolls, the estate was entire in 1709, but in 1740 it had dwindled to less than a fourth, and we then see a generally new order of proprietors.

The chief purchaser of the dismembered Blackbarony estate was the Earl of Portmore, a personage no way connected with the district, and of whom and his titled successors all recollection is lost. We may give a passing word to this now forgotten family. Sprung from the Robertsons of Strowan, and becoming a soldier of fortune, the first of the family comes into notice as fighting in the Dutch service at the end of the seventeenth century, at which time he had adopted the surname of Colyear. Sir David Colyear came to England with William III., and for his services was raised to the peerage as Lord Portmore. Afterwards, 1703, he was created Earl of Portmore. By him or his son and successor, a large section of the Blackbarony estate was acquired, including that part on the south near the modern Portmore House ; the family also acquired the barony of Aberlady. In 1835, family and earldom were extinct, but long before that event, the several estates just referred to were, through the pressure of necessity, disposed of.

Among all the good bargains of land it is our pleasant lot to record, none, we think, can be compared with that about to be mentioned. In 1798, the Portmore possessions in Haddingtonshire and Peeblesshire were purchased for £22,000, by Alexander Mackenzie,1 who, in 1799, sold the Haddingtonshire portion, comprehending the barony and village of Aberlady, to the Earl of Wemyss, for .£24,000.* Where, alas ! whether at public auction or by private arrangement, is such a marvellous bargain now to be secured ? The portion in Peeblesshire, formerly a part of Halton-Murray, consisted of East and West Lochs, Kingside, Courhope, Cloich, Shiplaw, and Over Falla, in the parish of Eddleston, and East and West Deans' Houses, in the parish of Newlands. Courhope and Cloich, and also East and West Deans' Houses, have been latterly disposed of for considerable sums.

Alexander Mackenzie, the fortunate purchaser of the Portmore estate in 1798, was a writer to the Signet in Edinburgh, and descendant of Sir Alexander Mackenzie of Garioch. Getting the Peeblesshire property, as it may be said, for nothing, neither he nor his immediate successor made much of it, in consequence of the lands being let on exceedingly long leases at a very insignificant rent At the decease of Mr Mackenzie, the lands were inherited by his son, Colin Mackenzie, deputykeeper of the Signet, who had a large family by his wife, Elizabeth, daughter of Sir William Forbes, Bart., of Pitsligo. The eldest son, William Forbes Mackenzie, who succeeded in 1830, was for some time member of parliament for the county, and enjoyed a certain notoriety by having his name associated with the well-known Public-house Act for Scotland. When retired from public life, Mr Mackenzie died suddenly in 1862, and was succeeded by his only chifd, the present Colin James Mackenzie of Portmore.

By Colin Mackenzie, the son of the purchaser, the estate was improved by planting and other costly operations. He also enlarged it by acquiring Whitebarony and other lands in the neighbourhood ; but the higher district remained, for the greater part, in a dreary backward condition — a circumstance ascribed to the perniciously long leases at rents which offered no stimulus to improvement. That the leases on this property, protracted till about 1834, should have been attended with consequences so different from what ensued in regard to the Neidpath estate, is a fact not unworthy of notice. Although limited in dimensions by the sales above referred to, the estate of Portmore had, in 1863, a valued rental of £3720, qs. For many years, the family of the proprietor resided in a small house at Harcus, but recently this was abandoned for a new and commodious mansion, in a handsome style of architecture, situated on an elevated ground, and commanding an extensive view southwards down the valley. Adorned by well-grown woods, the grounds around Portmore possess some degree of interest by including the ancient British fort, known as Northshield Rings. They are further attractive by bordering on a pretty sheet of water, two miles in circumference, now known as Portmore Loch. In Blaew's map, the outlet of this mountain tarn is marked as towards Eddleston Water. It has no exit in this direction. From its northern extremity flows a burn as a feeder of the South Esk, which, uniting with the North Esk at Dalkeith, falls into the sea at Musselburgh. In the description of the lake by Blaew, it is said to abound in fish, principally eels, which, rushing out with impetuosity in the month of August, are caught in such great numbers by the country people, as to be a source of much profit. In the present day, perch, pike, and eels are stated to be found in the loch, but not in that overwhelming abundance narrated by the Dutch chronicler. Dundreich, with its huge rounded form, rises on the south ; and immediately adjoining, in a south-easterly direction, is the hill called Powbeat, on which, it is alleged, there is a spring so deep and mysterious, as to give rise to the notion that the hill is full of water. The common people in the neighbourhood amuse themselves with a speculation as to the mischief which would be occasioned were the sides of the hill to burst. Observing the direction of the valley of the South Esk, they conclude that the deluge would flow towards Dalkeith, carrying off, in the first place, three farms, and finally sweeping away several kirks in its destructive course. These whimsical conjectures are thrown into a popular rhyme, as follows :

' Powbate, an' ye break, Tak' the Moorfoot in your gate, Huntly-cot, a' three, Moorfoot and Mauldslie, Five kirks and an abbacie.'

The five kirks are those belonging to the parishes of Temple, Carrington, Borthwick, Cockpen, and Dalkeith ; and the abbey (which shews the antiquity of the rhyme) is that formerly existing at Newbattle.

Cringletie House

The estate of Cringletie, increased by recent acquisitions, lies generally to the south of Blackbarony, the distance from Darn Hall to Cringletie House being about two miles. The Murrays, the present proprietors, are, as above described, descended from Sir Alexander Murray of Blackbarony (time of Charles I. and Commonwealth), by a second marriage with Margaret, daughter of Sir David Murray of Stanhope. John, the son of this pair, received from his' father, in 1667, the lands of Upper and Nether Kidston, purchased by him only a year before, and which lands, along with Easter and Wester Wormiston, were erected into a barony called Cringletie, in 1671. Kidston, in its various parts, at one time belonged to Lord Fleming, and afterwards to the Earl of Douglas, who conveyed the lands to a family named Lauder. These Lauders appear to have had considerable possessions about Eddleston Water. In the returns, under date 1603, mention is made of ' Alexander Lauder of Haltoun,' heir of Alexander Lauder, who was killed at the battle of Pinkie ; and in 1655, there was a ' John Lauder of Hethpool.' It is interesting to note how this family, which cut a figure in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, culminated, waned, and disappeared. As early as 1512, there are writs embracing the Green Meldoun, which, from its description, is assumed to be Hamilton or Hamildean Hill. By a charter of resignation and novodamus, 1610, this hill, the subject of future contests with the town of Peebles, was associated with Kidston and Wormiston, in virtue of which it was adjudged to be part and parcel of the Cringletie estate, and as such it remains till the present day.

As the Lauders vanish from the stage, the Murrays come into view. John Murray, the first of Cringletie, was succeeded by his brother Alexander, who had two sons — Alexander, his heir, and Archibald, who was bred an advocate, and to whose descendants we shall afterwards refer. Alexander, who succeeded to Cringletie, officiated for some time as sheriff-depute of Peeblesshire under the Earl of March, and represented the county in three several parliaments. Alexander, his eldest son, succeeded him, and acquired distinction as an officer in the army, in which he rose to the rank of lieutenant-colonel. He held a command at the siege of Louisburg, capital of Cape Breton, and afterwards served with distinction under General Wolfe, at the battle of Quebec, 1759. He commanded the grenadiers at the landing of the army, on which occasion he received four shots through his clothes without being hurt ; and in the battle which ensued he distinguished himself with great gallantry.1 At this time, Colonel Murray was married, and his wife, a daughter of Sir James Stewart of Goodtrees, Bart., accompanied him in his Canadian campaign. He had two sons, Alexander and James Wolfe, and a daughter. The second son, born in January 1759, was named after General Wolfe, who acted as his godfather, and expressed a wish that the name of Wolfe might remain in the family. Colonel Murray died at the reduction of the island of Martinique, 1762, and was succeeded by his eldest son, Alexander.

James Wolfe Murray, who was educated for the Scottish bar, at which he passed as advocate in 1782, became afterwards sheriff of Peeblesshire. Towards the end of the century, he bought the family estate for £8000, from his brother, Alexander, who died without issue in 1822.* It is mentioned, that in making this purchase, Mr Murray was assisted by his uncle, an aged bachelor, Colonel James Murray, who will be remembered by old people about Peebles, for he lived for a number of years in Quebec Hall at the East Port, and died there in 1807. Of James Wolfe Murray, and his polite and agreeable manner, many still alive will vividly retain a recollection ; perhaps many more will remember his beautiful and remarkably clever wife. This

[West wished Colonel Murray to figure in his picture representing the death of Wolfe ; ' but the honest Scot refused, saying, " No, no ! I was not by ; I was leading the left." '—Wright's Life of Wolfe].

lady, Isabella Strange, was a granddaughter of Sir Robert Strange, celebrated as an engraver toward the end of last century. Strange's history is associated with some stirring events. He was born in Shetland in 1721 (his father having been connected with the Stranges or Strongs of Balcaskie, in Fife), and was, from his taste for art, sent to be apprenticed as an engraver in Edinburgh. There he formed an attachment to the charming Isabella Lumsden, sister of Andrew Lumsden, writer, who, from his Jacobite proclivities, became private secretary to Prince Charles Edward on his appearance in 1745. Miss Lumsden, a still more enthusiastic adherent of the Stuarts than her brother, would only promise to marry Robert Strange, on his engaging heartily in the rebellion, which he forthwith did — the duty more especially assigned to him being that of engraving bank-notes for the use of the rebel army. On the dispersal of the insurgents at Culloden, Strange, like others, fled for his life. It is related by his biographer, that on one occasion, being ' hotly pressed, he dashed into a room where the lady, whose zeal had enlisted him in the fatal cause, sat singing at her needle-work, and failing other means of concealment, was indebted for safety to her prompt intervention. As she quickly raised her hooped gown, the affianced lover disappeared under her ample contour, where, thanks to her cool demeanour and unfaltering notes, he lay undetected while the rude and baffled soldiery vainly ransacked the house.'

Escaping to France, Strange was compensated for his misadventures, by marrying Miss, Lumsden in 1747. For many years he carried on business as an engraver in Paris, where his finest works were produced. He and his family at length came to England, where there was no longer any danger on account of the affair of 1745. Coming into favour as an artist with George III., he received the honour of knighthood in 1787. He died, 1792. Sir Robert Strange had a large family. His eldest son was James Strange, whose first wife was Margaret Durham of Largo, by whom he had a daughter, Isabella. This child, sent to live for some time with her grandfather, at his house in Great Queen Street, Lincoln's Inn Fields, is described as having inherited the sparkling wit, vivacity, and worth of her grandmother, Lady Strange, to whom she was much attached. Such was Isabella Strange, who, in 1807, became the beautiful wife of James Wolfe Murray of Cringletie. Held in esteem, Mr Murray was raised to the bench of the Court of Session, in 1816, when he adopted the judicial title of Lord Cringletie. His lordship died in 1836, leaving a family of four sons and eight daughters — all noted, in a singular degree, for their unaffected manners and sprightliness of disposition.1 Mrs Murray, his widow, died at Paris in 1847. Lord Cringletie was succeeded by his eldest son, James Wolfe Murray, the present proprietor.

We now return to Archibald Murray, advocate, brother of Alexander, the laird, second in descent from Blackbarony. He acquired the estate of Nisbet, two miles west from Edinburgh, which he called Murrayfield, and this designation it still retains. By his wife, a daughter of Lord William Hay, younger son of John, Marquis of Tweeddale, he had a son Alexander,, who, also, was reared to the profession of the law, and succeeded his father as sheriff-depute of Peeblesshire in 1761. Rising at the bar, he was appointed a judge in the Court of Session in 1782, when he adopted the title of Lord Henderland, from the estate of the same name in Megget, which had already become a possession of the family. The wife of Lord Henderland was a daughter of Sir Alexander Lindsay of Evelick, baronet, and niece of the first Earl of Mansfield. By this lady he had two sons — William, who inherited his property of Henderland, and John Archibald. This second son, who lived to inherit his brother's patrimony, will long be remembered for his genial qualities, and the part he played in politics in Edinburgh in the early part of the present century.

Bred to the law, like his father and grandfather, John Archibald Murray was appointed Lord Advocate in 1834, and after being some time member of parliament for the Leith district of burghs, was raised to the bench in 1 839, when he took the title of Lord Murray. He was at the same time knighted. From this time till his death, in 1859, Lord Murray was one of the notabilities of Edinburgh. William Murray, who predeceased his brother, left Henderland to the representative of the main line of the family, James Wolfe Murray of Cringletie, subject, however, to some arrangements on the part of Lord Murray. On the death of Lady Murray, the estate was handed over, free, as originally destined. Among the property left to Lord Murray by his brother, was Ramsay Lodge, on the Castle Hill of Edinburgh, which William Murray had received as a bequest from his cousin, Major-general Ramsay, whose mother, Margaret Lindsay, was a sister of the wife of Lord Henderland. This classic mansion, where lived and died the author of the Gentle Shepherd, was sold at the death of Lady Murray.

Henderland was but a short time in possession of Mr Murray. In 1862, he excambed it with the Earl of Wemyss for Courhope and Cloich, which his lordship bought that year for £25,100 ; Mr Murray giving, in addition, the sum of £1550 to adjust the exchange. The sale of Courhope and Cloich, a pastoral tract adjoining Cringletie, offers one of the many instances of the rise in the value of property of this nature ; for as lately as 1840, it had been disposed of for £13,000. Extended by this acquisition, the Cringletie estate comprehends a considerable part of the high grounds west of the vale of Eddleston, including Upper and Nether Stewarton. Southwards, within the parish of Peebles, it includes Upper and Nether Kidston, also Kidston Mill ; the buildings of this last-mentioned place forming a picturesque group close upon the line of railway. In 1863, the valued rental of the estate was £2439, 4s- Mr Murray inherits the small property of Westshield, in Lanarkshire, which had been purchased by his father, Lord Cringletie, and formed originally part of the Coltness estate.

Cringletie House, situated on a plateau at the top of a steep bank, rising from the right bank of Eddleston Water, is said by Armstrong to be environed by ' an extensive plantation, to shield it from the rude blasts of Boreas, and add useful and ornamental value to its mature improvements.' Since this was written, the woods about Cringletie have increased in extent and beauty, and much has been done to add to the general amenity of the grounds. The old mansion having lapsed into a bad condition, the present proprietor adopted the wise policy of pulling it entirely down, and building a new one on a better scale, instead of attempting a mere reparation. An edifice in the picturesque old Scottish manor-house style, built of reddishcoloured sandstone, as represented in the adjoining cut, fig. 50, was completed in 1863, and is now occupied by Mr Murray and his family. The house contains some family pictures by good masters. Among these there is a remarkably fine portrait of Thomas Lord Erskine by Gainsborough, and one of his brother, the Hon. Henry Erskine, by Raeburn. The Countess of Buchan, mother of the Erskines, being a sister of Lord Cringletie's mother, they stood in the relationship of cousins to the Murrays, and in boyhood occasionally visited Cringletie to spend their summer holidays. A story is told of a dumb ' spae-wife ' calling when they were there, and indicating by signs, in a remarkable manner, what was to be Thomas Erskine's fortune. He would be a sailor, but (with a shake of the head) that would not do ; he would be a soldier, but (another shake) that also would not do ; lastly, affecting to read and harangue, and. graciously patting him on the back, she shewed by that means he was to be a great man ; whereupon the youthful spectators of the sport burst into the derisive shout : ' Man, Tarn, ye '11 be but a minister after a'. ' Such remains a favourite anecdote at Cringletie, and we must allow that it faithfully pictures the career of the great forensic orator, who, after being in the navy and army, lived to be Lord Chancellor of England.

The access to Cringletie has been lately much improved, by carrying a high bridge across the river and railway, thereby lessening the extreme steepness of the approach. With glimpses from amidst the surrounding trees, the house commands a fine view down the valley towards Peebles, and northwards in the direction of Portmore.

On the high grounds, on the opposite side of the Eddleston from Cringletie, lies the property of Windilaws, augmented in a small degree by part of Glentress Common, in the manner formerly alluded to. Among the other lesser properties in the parish are Harehope, remarkable for its British hill-forts, now belonging to John Inch, also a farm usually called Cowie's Linn, which pertains to Sir Cowie's Linn. G. Graham Montgomery, Bart., of Stanhope. This last-mentioned property, situated to the north of Darn Hall, was long, as in the case of the Portmore estate, in a backward condition, but has lately been in a course of improvement. Through it there pours a considerable burn, a feeder of the Eddleston, celebrated for a waterfall of about thirty-five feet, from which the farm has been designated. Cowie's Linn, which possesses much picturesque beauty. It is situated in a solitary ravine, at the distance of about half a mile from Early Vale, on the public road, and forms a favourite resort of summer visitors.

The modern village of Eddleston, situated near the gateway to Darn Hall, is a model of neatness and good order ; and we should not omit to state, that neither here nor in any part of the parish is there a single public-house — a contrast with what is mentioned by Armstrong in 1775, when there were three houses of public entertainment in the village. Till within the present century, Eddleston was noted for an annual fair on the 25th September, which is now abolished. The spot on which it was held, is occupied as one of the stations of the Peebles Railway. The Eddleston Water, in its course of four miles from the village to Peebles, affords some good points for the pencil of an artist.

Source: A history of Peeblesshire by William Chambers (1800-1883) - Pages 345-365 - Murrays of Elibank (Blackbarony) and Cringletie.

Note: Alexander Erskine Erskine-Murray was born on 9th December 1832. He was the son of Hon. James MURRAY and Isabella ERSKINE. He was given the name of Alexander Erskine MURRAY at birth. His name was legally changed to Alexander Erskine ERSKINE-MURRAY.

Private Burial Ground of the Murrays of Elibank

National Grid Reference NT(36) 233471

Arthur Cecil Murray, 3rd Viscount Elibank

THE FOUNDATION of the Murray Clan Society took place in Edinburgh on the night of Wednesday 17th January 1962 at the Royal Overseas League, 100 Princes Street. This was the inaugural meeting of the Society: "It was unanimously decided that a Clan Murray Society should be formed and the following office-bearers were elected: Hon. President, Colonel The Hon. the Viscount Elibank, CMG, DSO; President, Major Alastair Erskine-Murray, MA, FSA Scot.

Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Cecil Murray, 3rd Viscount Elibank, CMG, DSO (27th March 1879 – 5th December 1962) [pictured above] was a British army officer and politician. Murray was the fourth son of (1st) Viscount Elibank of Selkirkshire and his wife Blanche Alice née Scott of Portsea, Portsmouth, Hampshire. The family moved to Dresden in Germany in 1886, and he received his early education in the city. He was a student for at least some time at Sunningdale School in Berkshire.He entered the Royal Military College Sandhurst and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Indian Staff Corps on 20th July 1898. In the same year he became Aide-de-Camp to the Lieutenant Governor of Bengal, Sir John Woodburn. He served as part of the international force that intervened to suppress the Boxer Rebellion in China in 1900 and commanded a Mounted Infantry Company, protecting the Sinho-Shanhaikwan Railway. He subsequently served on the North-West Frontier and in Chitral. In 1907 he was promoted to captain in the 5th Gurkha Rifles (Frontier Force).

In March 1908, John William Crombie the member of parliament for Kincardinshire died, and Murray was selected by the Liberal Party to contest the resulting by-election. He won the seat, and remained MP for Kincardineshire and its successor constituency, Kincardine and Aberdeenshire West, until 1923. From 1910 until the outbreak of war in 1914 he was Parliamentary Private Secretary to Sir Edward Grey, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs.

He served in World War I in France and Belgium from 1914 to 1916 with the 2nd King Edward's Horse, was mentioned in despatches and awarded the Distinguished Service Order in 1916. He was Assistant Military Attaché in Washington from 1917 to 1918, and was awarded the Companion of the Order of St. Michael and St. George (CMG) in 1919. Although a member of the Liberal Party which formed part of the coalition government, Murray became a stern critic of the policies pursued by the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George. He lost his seat at the 1923 general election. Following the loss of his Commons seat he continued to take an active interest in politics, in particular foreign policy, and wrote a number of books and pamphlets on the subject. He became a director of the London and North Eastern Railway from 1923 to 1948 and of Wembley Stadium. When the Liberal Party split over support for the National Government in 1931, Murray initially remained with the main section of the party in opposition, but joined the National Liberals in 1936.

In 1945 Murray published a political memoir, Master and Brother: Murrays of Elibank. In 1951 he succeeded to two titles: the Viscount of Elibank and the Lord Elibank of Ettrick Forest, following the death of his elder brothers. He was a Member of the Royal Company of Archers. In 1931 he married the actress Faith Celli. The couple had no children, and she died in 1942. He died in December 1962. On his death, the title of Lord Elibank and the baronetcy passed to his kinsman James A. F. C. Erskine-Murray (great grandson of the seventh Lord Elibank), the Viscountcy becoming extinct.

Alastair Erskine-Murray, 13th Lord Elibank

James Alastair Frederick Campbell Erskine-Murray, 13th Lord Elibank, was born on 23 June 1902.1 He was the son of James Robert Erskine-Murray and Alleine Frederica Florinda Gildea. He was educated at Harrow School, Harrow, London, England. He was educated at Royal Military College, Sandhurst, Berkshire, England. He gained the rank of commander in 1922 in the Highland Light Infantry. He graduated from Glasgow University, Glasgow, Lanarkshire, Scotland, with a Master of Arts (MA). He fought in the Second World War. He was appointed Fellow, Society of Antiquaries, Scotland (FSA Scot.) He was appointed Fellow, Zoological Society Scotland (FZS). He succeeded as the 13th Baronet Murray, of Etrick Forest, County Selkirk [1628] on and as the 13th Lord Elibank, of Etrick Forest, County. Selkirk [1643] on 5th December 1962. He died on 2nd June 1973 aged 70, unmarried.

Alexander Murray of Elibank (1712-1778)

Soldier and Jacobite agent

The most likely candidate for the “Alexander Murray Esq” listed in the Land Tax Registers for a house in Brook Street is Alexander Murray of Elibank, the Jacobite agent. He was the fourth son of the 4th Lord Elibank and brother of Patrick Murray, 5th Lord Elibank. He received a commission in the 26th Regiment of Foot (the Cameronians) in 1737, rising to the rank of Lieutenant, and he made an advantageous marriage which brought him £3,000 per year. Horace Walpole described Murray and his brother, Lord Elibank, as...

“...such active Jacobites that if the Pretender had succeeded they would have produced many witnesses to testify their great zeal for him… [yet] so cautious that no witnesses of actual treason could be produced by the Government against them”.

Although he was not active during the 1745 Rising, Murray afterwards lent money to Prince Charles and, during the Prince’s secret visit to London in 1750, was incarcerated in Newgate for inciting a political disturbance in support of an anti-government candidate. When he was freed in June 1751 Murray drove to his brother’s house in Henrietta Street surrounded by crowds and carrying a banner reading “Murray and Liberty”, shortly afterwards fleeing to exile in France before he could be recommitted to prison. The following year Murray gave his name to the so-called “Elibank Plot”, an attempt to capture the Hanoverian royal family from St James’ Palace and replace George II with the Old Pretender. He was created Jacobite Earl of Westminster in 1759. Murray remained in exile until 1771 when he was permitted to return to Britain, and then resided chiefly at Taplow House in Buckinghamshire until his death in 1778.

Murray’s house was the last on the south side of Brook Street west of Bond Street, a few doors down from Handel. During his time in exile the house was probably sublet, as was his estate at Taplow, for we know that Murray remained engaged via correspondence in political and cultural affairs in Britain while residing in France. After Murray’s death the house appears to have been occupied (1778-1779) by his nephew, Alexander Murray (1747-1820), who succeeded as 7th Lord Elibank in 1785