Gallery

THE 3rd Duke of Atholl and family by Johann Zoffany (1733-1810) can be seen above (left) on the banks of the River Tay. It is believed that local artist Charles Steuart painted the background, the canvas was then despatched to London for the portraits to be added. Zoffany was a celebrated artist patronised by royals and known for his ability to capture the sitters' character. The painting's invoice states that Zoffany charged 20 guineas per person, although he did not charge for the family pet lemur (Tom) who can be seen in the tree. It is also interesting to note the pentimento effect at the legs of the Duke and of the Marquis beside him, but even more noticeable by the swan. The current Duke is descended from the tree-climbing 3rd son, later to become the Bishop of Rochester. A Family Portrait of John, 4th Duke of Atholl with his First Wife, the Hon. Jane Cathcart, is seen below (centre). The Duchess is holding John, Marquis of Tullibardine, later 5th Duke of Atholl with Lady Charlotte aged five and Lady Amelia Murray as a baby. Looking on is Alexander Crerar, gamekeeper to the Duke, with two dogs and a dead stag. Highland Wedding at Blair Atholl 1780, by David Allan seen below (right). Neil Gow, the celebrated violinist, composer and collector is amongst the musicians. Gow's services were retained by the Duke of Atholl for 5 pounds a year. The tartan worn in this picture was done so illegally, highland dress being outlawed until the Act was repealed in 1782.

Can you name all the Murrays portrayed in these pictures?

CONGRATULATIONS to Stefani and Kate from Queensland, Australia (Murrays through their mother and grand-mother), who took the plunge in trying to name all the Murrays portrayed in the pictures below (the first to do so). Unfortunately, there was one that they named incorrectly but it was designed to be difficult with an answer that is not immediately obvious. The fourth painting is a portrait of the Hon. Angela Campbell-Preston (1910-1981), painted a year before her death. Mrs. Angela Campbell-Preston was the mother to the 10th Duke of Atholl (George Iain Murray). Angela moved to Blair Castle in 1945 after her husband, Colonel George Anthony Murray died. She had a shrewd business mind, sound judgement and a good head for figures. After the war when the castle reopened to visitors, she hired new managers for every department, not just the castle but the farms and woods too. Mrs. C. P., as she was affectionately known, was determined that the estate should run as a modern self-sufficient business. We have sent Stefani and Kate a limited-edition print (unframed) of Castle Cluggy painted by Scottish artist Kimberley Smith as they made such a great effort and named so many portraits correctly.

Lord Mungo Murray

THIS IMPORTANT Scottish portrait of a Highland Chieftain by John Michael Wright is thought to be the earliest major painting to depict a sitter full-length in Highland dress. The subject is Lord Mungo Murray (1668-1700), fifth son of John Murray, 2nd Earl of Atholl, and Lady Amelia Sophia Stanley, daughter of the 7th Earl of Derby. Mungo Murray was involved in military expeditions in the north of Scotland in the 1680s and 1690s. Spurned in love, he set sail in 1699 for New Caledonia (in present-day Panama) as part of the ill-fated Darien scheme by the Company of Scotland Trading to Africa and the Indies. Shortly after his arrival in early 1700, Murray, aged just 32, was killed by Spanish forces who had laid claim to the territory. Wright’s portrait of Murray was painted in Ireland, where the artist had travelled to escape Catholic persecution.

Wright’s portrait of Murray was painted in Ireland, where, as a Roman Catholic, the artist had travelled to escape persecution in London. It is thought to have been a companion picture to Wright’s painting Sir Neil O’Neill as an Irish Chieftain, now in the Tate collection, London. Wright shows Murray, aged about 15, dressed for hunting in a féileadh-mór (a precursor to the kilt), woven with a subtle red, yellow and green sett. On his upper body he is clothed in a wool doublet embroidered with silver and silver-gilt threads, demonstrating his wealth, status and nationality as an aristocratic Highland Scot. In his right hand he holds a Scottish long gun made for hunting, while a sword and dagger hang below his waist. His servant, in the background, carries a longbow, used for hunting deer.

Portrait of Dido Belle and Lady Elizabeth Murray

and the attribution to David Martin (1737-1797) by Valeria Vallucci

David Martin, Portrait of Dido Belle and Lady Elizabeth Murray, late 1770s, Scone Palace, Perth

The recent Royal Academy exhibition Entangled Pasts 1768-Now: Art, Colonialism and Change was part of a global effort by art institutions to re-examine and re-interpret both history and art in light of new understandings of colonialism. The exhibition explored the Royal Academy’s own associations with British imperialism and the relationship between ‘modernity and coloniality.’[1] It presented an impressive range of contemporary artifacts and historic paintings that have been recognised around the world as providing valuable insights into Black British history and the Atlantic slave trade. Included amongst them was a portrait of the late 1770s by David Martin (1737-1797) depicting Dido Belle (1761-1804) and Lady Elizabeth Murray (1760-1825). The portrait is one which the gallery is very familiar with; in 2018 Philip investigated and confirmed its authorship on an episode of BBC’s Fake or Fortune? (Series 7). On loan from Scone Palace (Perth), the Scottish seat of the Earls of Mansfield, it once hung at Kenwood House and was loosely attributed to Johann Zoffany (1733-1810). Dido and Elizabeth were great-nieces to the Lord Chief Justice of the King’s Bench, William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield (1705-1793).

Dido was the daughter of Admiral Sir John Lindsay (1737-1788), Commander-In-Chief of the British Navy, and an enslaved woman called Maria. She was brought up between Kenwood House and Bloomsbury by the childless Mansfields together with her cousin Lady Elizabeth, who was also a maternal orphan. The two girls kept each other company, were educated together, but had different roles and allowances within the family. Dido contributed to the running of the house, sometimes acting as secretary to her great-uncle and managing the dairy and poultry yard.[2] An obituary printed in 1788 stated that Dido’s ‘amiable disposition and accomplishments have earned her the highest respect from all his Lordship’s relations and visitants’.[3]

At the Royal Academy exhibition, the double portrait was shown in the section ‘Sites of Power: Conflict and Ambition’ to highlight the ambivalence of Lord Mansfield’s attitude to slavery.[4] Politicians and actors admired Mansfield’s prodigious oratorical skills. He was also highly respected by tradesmen for his swiftness of action and common sense.[5] During the James Somerset case of 1772 he famously denounced slavery as being ‘so odious, that nothing can be suffered to support it’.[6] Yet he was always careful not to damage businesses that traded overseas. This conflict is explored well in Belle (2013), the romantic period drama directed by Amma Asante based on Dido’s story, which focuses on Lord Mansfield’s ruling in the Zong case (1783) and on the double portrait as evidence of his thinking.[7]

The double portrait received considerable media attention after the release of Belle (2013) and the publication of Paula Byrne’s Belle: The True Story of Dido Belle (2014). The rediscovery of Dido Belle’s story – the daughter of a slave who became a member of an aristocratic British family – inspired a wider conversation about race, slavery, and abolition. The painting, in turn, is now recognised as being of national historical importance.

After receiving so much exposure, in 2018 the Mansfield family engaged Philip and the Fake or Fortune? team to try and establish the correct attribution of the portrait. After extensive research in the Mansfield Archive, and thanks to in-depth stylistic and forensic analysis, they established that the portrait was painted by the Scottish portraitist David Martin (1737-1797).[8]

An inventory dated 1796 shows that just three years after Lord Mansfield’s death, the portrait was no longer on display at Kenwood House and its artist was completely unknown.[9] Early twentieth-century inventories do not even mention Dido Belle by name, suggesting she had been completely forgotten.[10]

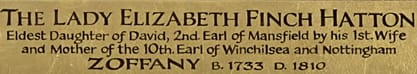

When the portrait was later reframed at Scone Palace the accompanying plate erased her completely:

Still taken from BBC One, Fake or Fortune?, ‘A Double Whodunnit’, Series 7, Episode 4.

The breakthrough came when Philip inspected Lord Mansfield’s private account books from the late eighteenth century. These revealed a payment of £200 to David Martin on 8th October 1776. By comparing the portraitwith another portrait by David Martin in the Mansfield collection, Lady Margery (1760s), he noticed a series of striking similarities.

For instance, the small colourful flowers catching the light on Lady Elizabeth’s hair echo Lady Margery’s hair adornments. Both ladies are painted with bright red ruby lips and elongated faces. As Philip explained, portrait painters of the time tended to impose their own ideas of how a subject should look, and this is an example of Martin’s ideas on how to paint aristocratic ladies. He also noticed similarities in the embroidery, translucence, and folds of the gauzes in both works, as well as the playful positioning of Dido’s right hand which recalls that of Lady Margery’s in her portrait.

After Philip established that an attribution to Martin was highly possible, specialist conservationists from the University of Northumbria were called in to collect samples from both portraits. They found that the white paint and the vermillion in both paintings were an exact match. As a result, Brian Allen, an authority in eighteenth century British portraiture, endorsed the attribution. Allen was particularly convinced by the distinctive handling of the silks, satins and muslins which he considered an influence from Alan Ramsay, who taught Martin.

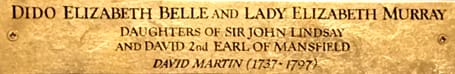

Since this endorsement, the portrait has received a new name plate which tells a more complete story of the work and those involved in its creation.

Detail of David Martin's Portrait of Dido Belle and Lady Elizabeth Murray, late 1770s.

[1] Entangled Pasts 1768 - Now: Art, Colonialism and Change, Royal Academy of Arts, London 3 February - 28 April 2024, pp.6 and 12.

[2] Kenyon Jones, C. (2010) ‘Ambiguous Cousinship: Mansfield Park and the Mansfield Family’ in Persuasions On-line, vol. 31, no.1. Available at: https://www.jasna.org/persuasions/on-line/vol31no1/jones.html? (Accessed 17 April 2024).

[3] London Chronicle, 7 June 1788. Quoted in Byrne, p.210.

[4] Entangled Pasts 1768 - Now: Art, Colonialism and Change, p.65.

[5] Byrne, pp.111-120.

[6] James Somerset was a young African slave purchased in Virginia in 1749 by merchant Charles Stewart. In 1769 Stewart brought Somerset back to London. Soon afterwards Somerset was baptised and decided to leave his master. At the end of 1771, under Stewart’s orders, Somerset was kidnapped to be sent back to Virginia as a slave. Lord Mansfield ruled that it was unlawful to transport Somerset out of England against his will. His decision interpreted as a declaration that slavery was unlawful in England, boosting the abolition movement on both sides of the Atlantic. Many contemporary commentators believed the Somerset case was influenced by the presence of Dido Belle in Lord Mansfield’s household.

[7] In 1781, because of a shortage of water, more than 130 enslaved African people were murdered by the crew of the Zong by being thrown overboard in chains. Zong’s owners claimed insurance for their maritime commercial loss, but the insurers refused to pay. Lord Mansfield ruled the loss was the result of a series of errors for which the crew was responsible. The case established that enslaved people could not be treated as ‘chattel’ and was a key moment in the development of the abolition movement. In the movie Belle, with considerable artistic licence, Dido learns from Mr Davinier, a passionate abolitionist lawyer, that for powerful traders, enslaved people can be worth more dead than alive, so human “cargo” should not be insured. Meanwhile, Lord Mansfield has to judge if such violent acts are ‘truly necessary’ for the safety of a ship. In the film this creates tension between Lord Mansfield and Dido. She becomes convinced that, when push comes to shove, existing rules and social norms are ‘inconsequential’ for her uncle - and his commission of Portrait of Dido Belle and Lady Elizabeth Murray proves this.

[8] BBC One, Fake or Fortune?, ‘A Double Whodunnit’, series 7 episode 4.

[9] ‘Lady Elizabeth and Mrs. Davinier, without a frame’. Mansfield Archive, Inventory of Household Furniture etc at the Earl of Mansfield’s House Kenwood (1796), p.37. In 1793 Dido married John Davinier, a gentleman’s steward.

[10] ‘Portrait of Lady Finch-Hatton, eldest daughter of David the 2nd Earl of Mansfied, by his first wife, and mother of the 10th Earl of Winchelsea and Nottingham, seated in a garden with an open book and a negress attendant’. Mansfield Archive, Inventory of Sevres, Dresden & Other China & Ornamental Articles Being in Kenwood, Hampstead, The Property of The Right Hon.ble The Earl of Manfield (1904). In the 1910 inventory Dido Belle is not mentioned at all in the description of the painting.

© 2024 Philip Mould & Company